A few days ago I was going thru some old magazines and newspapers so that I could recycle them. While I was doing so, an article in an issue of Metro Pulse caught my eye (for non-Southerners and other aliens, Metro Pulse is the alternative weekly newsrag of Knoxville, Tennessee).

It seems that Congress is considering making several additions to our Interstate highway system. One of the proposed Interstate highways would be Interstate 3. Also known as the Third Infantry Division Highway, the I-3 would run from Savannah, Georgia, to Knoxville.

Given, this isn’t the only Interstate being mulled over by our leaders. Other additions to the Interstate system that were also part of the 2005 highway funding bill include Interstate 9 (a central California road that would go from the I-5 north split to Stockton) and Interstate 14 (initially to run from Natchez, Mississippi, east to Augusta, Georgia, although further extensions might take it west to Austin, Texas, and east to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina).

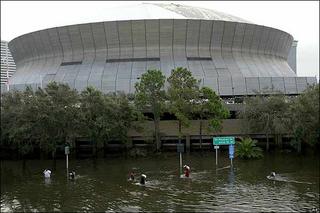

I have a couple of basic problems with this. The first is that Knoxville needs another Interstate like George Bush needs a third presidential term. Knoxville is already a key link in both I-75 and I-40, two major Interstate highways. These two Interstates intersect in Knoxville, to create a sprawling mess of congestion. My wife and I live in Chicagoland now. Knoxville’s Interstate traffic is easily just as bad as Chicago’s. Maybe even worse. In terms of air pollution, scruffy little Knoxville is also consistently among the top ten most polluted cities in the nation. These days the Smoky Mountains are more aptly the smoggy mountains.

The bigger problem with this, though, is that it shows just how short sighted our leadership really is. And how completely out of touch with reality our elected officials are. We are running out of oil and gas. Although it’s debatable whether oil production has peaked, it’s looking like it won’t be long until it does.

As James Howard Kunstler notes in his book The Long Emergency:

A few weeks ago, the price of oil ratcheted above fifty-five dollars a barrel, which is about twenty dollars a barrel more than a year ago. The next day, the oil story was buried on page six of the New York Times business section. Apparently, the price of oil is not considered significant news, even when it goes up five bucks a barrel in the span of ten days. That same day, the stock market shot up more than a hundred points because, CNN said, government data showed no signs of inflation. Note to clueless nation: Call planet Earth.

Carl Jung, one of the fathers of psychology, famously remarked that "people cannot stand too much reality." What you're about to read may challenge your assumptions about the kind of world we live in, and especially the kind of world into which events are propelling us. We are in for a rough ride through uncharted territory.

It has been very hard for Americans -- lost in dark raptures of nonstop infotainment, recreational shopping and compulsive motoring -- to make sense of the gathering forces that will fundamentally alter the terms of everyday life in our technological society. Even after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, America is still sleepwalking into the future. I call this coming time the Long Emergency.

Most immediately we face the end of the cheap-fossil-fuel era. It is no exaggeration to state that reliable supplies of cheap oil and natural gas underlie everything we identify as the necessities of modern life -- not to mention all of its comforts and luxuries: central heating, air conditioning, cars, airplanes, electric lights, inexpensive clothing, recorded music, movies, hip-replacement surgery, national defense -- you name it.

The few Americans who are even aware that there is a gathering global-energy predicament usually misunderstand the core of the argument. That argument states that we don't have to run out of oil to start having severe problems with industrial civilization and its dependent systems. We only have to slip over the all-time production peak and begin a slide down the arc of steady depletion.

The term "global oil-production peak" means that a turning point will come when the world produces the most oil it will ever produce in a given year and, after that, yearly production will inexorably decline. It is usually represented graphically in a bell curve. The peak is the top of the curve, the halfway point of the world's all-time total endowment, meaning half the world's oil will be left. That seems like a lot of oil, and it is, but there's a big catch: It's the half that is much more difficult to extract, far more costly to get, of much poorer quality and located mostly in places where the people hate us. A substantial amount of it will never be extracted.

The United States passed its own oil peak -- about 11 million barrels a day -- in 1970, and since then production has dropped steadily. In 2004 it ran just above 5 million barrels a day (we get a tad more from natural-gas condensates). Yet we consume roughly 20 million barrels a day now. That means we have to import about two-thirds of our oil, and the ratio will continue to worsen.

The U.S. peak in 1970 brought on a portentous change in geoeconomic power. Within a few years, foreign producers, chiefly OPEC, were setting the price of oil, and this in turn led to the oil crises of the 1970s. In response, frantic development of non-OPEC oil, especially the North Sea fields of England and Norway, essentially saved the West's ass for about two decades. Since 1999, these fields have entered depletion. Meanwhile, worldwide discovery of new oil has steadily declined to insignificant levels in 2003 and 2004.

Some "cornucopians" claim that the Earth has something like a creamy nougat center of "abiotic" oil that will naturally replenish the great oil fields of the world. The facts speak differently. There has been no replacement whatsoever of oil already extracted from the fields of America or any other place. Kunstler goes on to paint a pretty scary future, one in which life is we know it may be no more.

The circumstances of the Long Emergency will require us to downscale and re-scale virtually everything we do and how we do it, from the kind of communities we physically inhabit to the way we grow our food to the way we work and trade the products of our work. Our lives will become profoundly and intensely local. Daily life will be far less about mobility and much more about staying where you are. Anything organized on the large scale, whether it is government or a corporate business enterprise such as Wal-Mart, will wither as the cheap energy props that support bigness fall away. The turbulence of the Long Emergency will produce a lot of economic losers, and many of these will be members of an angry and aggrieved former middle class.

Food production is going to be an enormous problem in the Long Emergency. As industrial agriculture fails due to a scarcity of oil- and gas-based inputs, we will certainly have to grow more of our food closer to where we live, and do it on a smaller scale. The American economy of the mid-twenty-first century may actually center on agriculture, not information, not high tech, not "services" like real estate sales or hawking cheeseburgers to tourists. Farming. This is no doubt a startling, radical idea, and it raises extremely difficult questions about the reallocation of land and the nature of work. The relentless subdividing of land in the late twentieth century has destroyed the contiguity and integrity of the rural landscape in most places. The process of readjustment is apt to be disorderly and improvisational. Food production will necessarily be much more labor-intensive than it has been for decades. We can anticipate the re-formation of a native-born American farm-laboring class. It will be composed largely of the aforementioned economic losers who had to relinquish their grip on the American dream. These masses of disentitled people may enter into quasi-feudal social relations with those who own land in exchange for food and physical security. But their sense of grievance will remain fresh, and if mistreated they may simply seize that land.

The way that commerce is currently organized in America will not survive far into the Long Emergency. Wal-Mart's "warehouse on wheels" won't be such a bargain in a non-cheap-oil economy. The national chain stores' 12,000-mile manufacturing supply lines could easily be interrupted by military contests over oil and by internal conflict in the nations that have been supplying us with ultra-cheap manufactured goods, because they, too, will be struggling with similar issues of energy famine and all the disorders that go with it.

As these things occur, America will have to make other arrangements for the manufacture, distribution and sale of ordinary goods. They will probably be made on a "cottage industry" basis rather than the factory system we once had, since the scale of available energy will be much lower -- and we are not going to replay the twentieth century. Tens of thousands of the common products we enjoy today, from paints to pharmaceuticals, are made out of oil. They will become increasingly scarce or unavailable. The selling of things will have to be reorganized at the local scale. It will have to be based on moving merchandise shorter distances. It is almost certain to result in higher costs for the things we buy and far fewer choices. Of course, it’s easy to see Kunstler’s vision as nothing more than hype. History is filled with prophets who have been utterly wrong about the course of the future. Y2K was hardly the only unrealised disaster scenario painted for the turn of the millenium. One cannot underestimate humanity’s resiliance in situations like this one. We’re addicted to oil. And, as the current Presidential administration continues to show, addicts will do whatever it takes to get another fix.

And yet, I don’t see how we can keep going on like this. Today the average gas price in this country is $2.61. Two years ago at about this time it was $1.62. The year before, gas was nearly 24 cents per gallon cheaper than that. And don't be fooled. What you're paying at the pump is cheap. Europeans pay between six and seven U.S. dollars per gallon. Who knows what we'll all be paying in a decade or two. At that point, cars could easily be an unaffordable luxury.

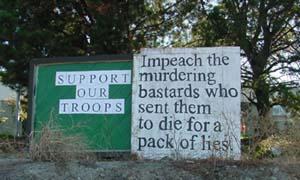

This has me wondering why we aren’t doing more to free ourselves of our oil and gas dependency. Iraq has the world's second largest oil supply. Iran has the fourth largest. So it’s no surprise what our policy is going to be in the near future. But given that our public transportation system is a joke, that most of us couldn’t survive for more than a week without Wal-Mart, and that we have no foreseeable replacement for oil and gas, shouldn’t Congress be pursuing interstate railroads and solar-powered buildings, instead of building roads that can’t possibly sustain automobiles in the future? |