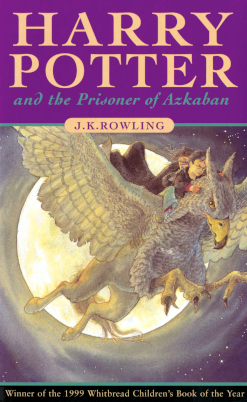

So we saw the latest Harry Potter film last weekend, which means I've since forsaken Jesus and started worshipping the forces of darkness. It's been pretty fun thus far. You should really try sacrificing a goat sometime. The blood tastes a little bitter if you aren't used to it, but the burning carcass has a very pleasing aroma. And I'm here to tell you that drunken orgies with barnyard animals are even wilder than you've imagined.

Only kidding, of course (or am I?). But the near back to back releases of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire and The Lion, The Witch and the Wardbrobe does mean that certain Christian groups will sing the praises of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkein, while simultaneously condemning J.K. Rowling for her glorification of magic and the occult. This attitude has died down a bit as the Potter series has progressed. But leave it to Focus on the Family to keep the embers burning.

Notes Plugged In, Focus on the Family's web site that "shines a light on the world of popular entertainment":

Nevertheless, no matter how skillfully the story gets told or how selfless, ethical and heroic Harry may be, it's impossible for me to invest myself in a series that glamorizes witchcraft. It’s easy to laugh when spineless bully Draco gets turned into a ferret. But it gets harder to make light of the sorcery when a potion requires that a man hack off his own hand, borrow a bone from a rotting corpse and drain blood from Harry’s arm.

Whether it’s grim treachery or comic relief, the film’s wall-to-wall sorcery is birthed from a faulty worldview that taps into the occult and never recognizes any divine authority. Unlike The Lord of the Rings and The Chronicles of Narnia, the entire series is built on a shaky spiritual foundation that sends young fans confusing messages about the morality and merits of the dark arts.

Of course, this is film four. Families that consider the supernatural sinew that binds Harry Potter together more trouble than it’s worth probably put the kibosh on it a long time ago. The ones still with it have decided either a) sorcery isn’t a big deal, or b) while they oppose real-life witchcraft, non-stop spells and incantations are acceptable when used as a literary device.

Even those in the "go with it" camp may find their patience tested with Goblet of Fire, the first film to warrant a PG-13 rating. It’s extremely grim at times and even features the death of a Hogwarts student. I was amazed at the number of small children seated around me in the theater. At what point will moms and dads who’ve been saying “yes” to voracious young Potter fans decide that things have gone too far? This could be it. Dumbledore warns Harry, “Soon we must face the choice between what is right and what is easy.” They’re not the only ones. There's a lot to chew on there. For instance, the reviewer has apparently forgotten that there really isn't any divine authority in The Lord of the Rings films. I'm also going to assume that the reviewer is comfortable with small children reading the Bible, a book filled with far more violence, sex and outright nastiness than anything I've witnessed in any of the Potter films. Goblet is a bit grim, to be sure, but it just doesn't quite stack up to a woman being gang raped and chopped into pieces.

But what I find most fascinating is what critics are either choosing to ignore, or are completely ignorant of, about Lewis' Chronicles of Narnia. Canadian film critic Peter Chattaway tackles the issue head on in a recent essay about the many threads of paganism found in the Narnia books. It's a great piece, and well worth reading in its entirety. But here are a couple of excerpts:

(M)any Christians will be watching (The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe) eagerly to see if director Andrew Adamson (or "son of Adam!") has respected the story's Christian elements.... Some of us, however, will be watching just as closely to see if the film has preserved those bits in C.S. Lewis's book that are a little more, shall we say, pagan. Presumably, the centaurs and fauns will look more or less like the mythological creatures depicted in ancient Greco-Roman art. But will, say, Mr Tumnus regale Lucy with stories of how the Roman god Bacchus filled the streams with wine when he feasted with the forest people?

-----------------------------

In all of his writings, Lewis was confronting a modern, skeptical, materialistic view of the world that had no room for the supernatural. Lewis believed that paganism and Christianity had more in common with each other on this point than either had with the modern, secularized world. In the essay 'Is Theism Important?', he wrote:

"When grave persons express their fear that England is relapsing into Paganism, I am tempted to reply, 'Would that she were.' For I do not think it at all likely that we shall ever see Parliament opened by the slaughtering of a garlanded white bull in the House of Lords or Cabinet Ministers leaving sandwiches in Hyde Park as an offering for the Dryads.

"If such a state of affairs came about, then the Christian apologist would have something to work on. For a Pagan, as history shows, is a man eminently convertible to Christianity. He is essentially the pre-Christian, or sub-Christian, religious man. The post-Christian man of our day differs from him as much as a divorcee differs from a virgin."

-----------------------------

Prince Caspian is ultimately about how the "Old Narnians" reclaim their land from Miraz and his entourage, with help from several sources. There is Aslan, of course, and also the ancient Kings and Queens themselves; the four children have become young again in our world, but when Caspian summons them to Narnia, they retain their royal authority.

But Narnia is also liberated with help from Bacchus and his drinking buddy Silenus, figures from Greco-Roman myth who were associated with drunken, mystical celebrations in the forest called "bacchanals". Bacchus and Aslan even dance together, along with Lucy, Susan, the nymphs and the maenads. And as they pass through Narnia, they destroy a boys' school and a girls' school where the children are taught a politically approved form of "history."

Lewis even seems to flirt with something like astrology. In more than one book, Narnian centaurs look for signs in the stars. In Dawn Treader, Eustace meets a man who is a "retired" star, and says, "In our world, a star is a huge ball of flaming gas." The star replies, "Even in your world, my son, that is not what a star is but only what it is made of."

Scenes like these might have been shocking to the early Christians, who saw themselves in direct competition with paganism, and sometimes condemned the gods as demons in disguise. Something that I suspect might be even more troubling to many Christians comes in the final book of Lewis' Narnia tales, The Last Battle. In it a foreigner named Emeth, a follower of the evil god Tash, is taken by Aslan to his heavenly kingdom. He receives this reward because he has done good, not evil. Those who do vile things, says Aslan, are in fact serving Tash. But those who do good things are in fact serving Aslan. So, despite his service to Tash, Emeth has really been serving Aslan, or Christ, by way of the fact that he has done good, not evil. Is it just me, or does that seem a bit contradictory to a Christianity that believes in faith, not works, and in one way to heaven? |

Comments on "Magically Delicious"

-

dufflehead said ... (11/30/2005 01:58:00 AM) :

dufflehead said ... (11/30/2005 01:58:00 AM) :

-

Jim Jannotti said ... (11/30/2005 07:24:00 AM) :

Jim Jannotti said ... (11/30/2005 07:24:00 AM) :

-

Anonymous said ... (11/30/2005 08:12:00 AM) :

Anonymous said ... (11/30/2005 08:12:00 AM) :

-

heather said ... (11/30/2005 08:46:00 AM) :

heather said ... (11/30/2005 08:46:00 AM) :

-

Dan Trabue said ... (11/30/2005 09:36:00 AM) :

Dan Trabue said ... (11/30/2005 09:36:00 AM) :

-

stc said ... (11/30/2005 12:08:00 PM) :

stc said ... (11/30/2005 12:08:00 PM) :

-

Anonymous said ... (11/30/2005 01:10:00 PM) :

Anonymous said ... (11/30/2005 01:10:00 PM) :

-

Cathie said ... (11/30/2005 06:00:00 PM) :

Cathie said ... (11/30/2005 06:00:00 PM) :

-

Jim Jannotti said ... (12/01/2005 07:45:00 PM) :

Jim Jannotti said ... (12/01/2005 07:45:00 PM) :

-

jasdye said ... (12/01/2005 11:09:00 PM) :

jasdye said ... (12/01/2005 11:09:00 PM) :

-

Wasp Jerky said ... (12/02/2005 10:41:00 AM) :

Wasp Jerky said ... (12/02/2005 10:41:00 AM) :

-

Jim Jannotti said ... (12/02/2005 12:40:00 PM) :

Jim Jannotti said ... (12/02/2005 12:40:00 PM) :

-

stc said ... (12/02/2005 01:41:00 PM) :

stc said ... (12/02/2005 01:41:00 PM) :

-

jasdye said ... (12/02/2005 04:11:00 PM) :

jasdye said ... (12/02/2005 04:11:00 PM) :

-

Wasp Jerky said ... (12/02/2005 05:11:00 PM) :

Wasp Jerky said ... (12/02/2005 05:11:00 PM) :

-

stc said ... (12/03/2005 06:16:00 AM) :

stc said ... (12/03/2005 06:16:00 AM) :

-

jasdye said ... (12/03/2005 10:38:00 AM) :

jasdye said ... (12/03/2005 10:38:00 AM) :

post a commentloved the post!

also to note, is that somehow the FoF reviewer seemed to miss the sorcery/magic in both LotR and CoN and the "grimness" of the hacking battle sequences in LotR.

Dang you dufflehead! You made the point I wanted to make. :-)

What I was going to say was Narnia, LOTR, Til We Have Faces (which is absolutely loaded with paganistic themes) are suffused throughout with magic and sorcery. What's the difference? Well it's that... actually there isn't any.

Add to that the fact that Rowling has liberally borrowed from Tolkein (and some from Lewis as well) for her books and I don't really understand how you can draw the kind of distinctions Focus is drawing.

And I want to see a film version of that gang rape and body part delivery sequence sometime, as well as Jezebel being thrown down from the tower and the dogs eating her. Yeah baby! What will Dobson say about that.

Even better, FOF seems to overlook the fact that LOTR is the ultimate gateway drug - not to heroin or cocaine of course, but to Dungeons & Dragons and eternal damnation....

Great post. I haven't read the books since becoming a pagan. I'll have to go back and read them with this worldview.

Right on. I like your last observation and it had crossed my mind the last couple of times I read it. Lewis indulging in a bit of Universalism?

I'm fine with it but surely Dobson et al aren't.

If there is any difference between Narnia and Harry Potter, it is this: C.S. Lewis was a Christian apologist, but JK Rowling is not. The incipient paganism of Narnia doesn't cancel out the Christian theological insights sprinkled throughout the Narnia series, because Lewis' ultimate allegiance was to Jesus Christ.

On the other hand, though Lewis is much-loved by evangelicals, he was not an evangelical himself. He did not believe that the events recorded in the book of Jonah were historical, for example.

I sometimes wonder what Lewis would believe if he were alive today. He was a product of his generation, when it seemed possible to reject some of the "peripheral" biblical stories, but still retain the essence of the Gospel.

Today, that is a much harder position to maintain with integrity. So how liberal would Lewis be, if he were alive today and looking at the current state of research into the Gospels?

Q

I haven't seen the Harry Potter movies or read the books -- but considering all the controversy & that evangelicals are carrying on about it, I think I just might. And, considering his biblical views on other topics, I never really did understand Lewis ending the Chronicles with universalism ... then again, it was just a story.

Frankie

It's a sad state of affairs when two childrens's books are at the center of American political "discourse."

A reminder that Lewis didn't actually end the Narnia books with a universalistic or paganistic message. Reread the end of The Last Battle to see his veiled way of revealing the Christian allegorical nature of the story.

He was writing from a Christian worldview, certainly. Though it was a worldview that many modern evangelical mouthpieces wouldn't recognize if it bit them. It embraced as within the pale many things about which modern evangelicalism might say, "do not handle! do not taste! do not touch!"

hmmm...

yeah, i always had trouble with that ending and the inclusive theology in it. although i certainly wouldn't call it universalism, neither could i ignore it. lewis was obviously trying to make a point in a rather heavy-handed way.

so what you're saying intrigues me, jim. could you expound, or tell me where i can get more on your perspective on the end (i'm assuming you're not speaking of the platonic, 'more real' heaven but of emeth's salvation).

That's a good point, Q. But I would also say that I don't think Lewis would say that his primary goal in writing the Narnia books was as an apology for Christianity. Or would he?

Likewise, Tolkein certainly used Christian symbolism and came from a Christian worldview, but he would seem to have more in common with Rowling than Lewis in approaching fiction (Rowling is a Presbyterian).

Speaking of symbolism, Christianity Today has a short piece about some of the Christian symbolism in the Potter series.

I was actually speaking of the actual end of the book, the last couple of paragraphs actually, where Aslan is transformed and where he reveals something to the children about why they are back in Narnia. "He no long appeared to them as a Lion." Sorry if I didn't make that clear.

I suppose it is a little heavy handed, but that's one of the reasons Tolkein despised allegory. It tends to feel like a sermon after a while, or at least like a moral fable. Nonetheless, Lewis uses the ending, I think, to remind us, or reveal to us, that though his worldview embraces a wide variety of perspectives, the center of that embrace is Jesus. This is quite consistent with his straight ahead explanations of his theology in many of his books.

I didn't want to include any spoilers since there are plenty of people out there who haven't read the Narnia books.

Kevin commented above that Lewis wasn't, or maybe was writing Narnia as an apologetic for Christianity. That's the thing about Leiws' apologetics, you often don't that this is what he's doing.

I'm not trying to say that there aren't universalits strains, and even paganistic themes in Lewis, there certainly are, only that Lewis seemed to be certain enough of God, specifically as manifested in Christ, that he could be quite comfortable roaming that ground.

Speaking of Christianity Today, the current issue (I received it sometime this week) has a Lewis cover story: C. S Lewis Superstar.

• I don't think Lewis would say that his primary goal in writing the Narnia books was as an apology for Christianity.

I think that's right. As I recall, Lewis always denied that the Chronicles of Narnia was an allegorical tale. But he must have meant allegory in the strict sense of the word, where every element of the story has a symbolic meaning. Pilgrim's Progress is an allegory in that (rather mechanical) sense.

Similarly, the Perelandra series has elements that correspond to the Gospel and elements that don't. Lewis wanted his works of fiction to tell a good story, without letting the theology spoil it.

Dare I suggest that this is another contrast between Lewis and contemporary evangelicals? — he wasn't nearly so earnest as they are. For Lewis (and Tolkein) it was OK to tell a good story for its own sake. He utilized insights from his Christian worldview to enrich the story — to add another layer of meaning — but I think that's the way he would put it.

The theological insights weren't the purpose of the books, just a bonus.

Q

yeah, that makes a lot of sense. i knew that lewis had said that his works weren't really allegory, but that never made sense. of course the lion was shaping up as the Christ figure. i suppose if you compare them to something truly heavy-handed (at least by today's standards) like pilgrim's progress, then it certainly doesn't come across in that understanding of allegory.

I think Lewis' take on it was not that Aslan was a Christ figure or a symbol for Christ, but that Aslan was Christ come to Narnia. Can anyone confirm that? Or is my delusional world starting to become a little too real?

Aslan was a Christ figure come to Narnia.

I hadn't heard that before, but I think it is consistent with Lewis' theology.

Lewis believed it is probable that there is life elsewhere in the cosmos. (Lots of intellectuals believe that today, as well, because we now understand that the cosmos is unimaginably vast.)

He theorized that some planets might never have "fallen". And I think (it's been a long time since I've read about this, so I'm not certain) he also figured that any other fallen planet would have its equivalent to Christ's atonement.

The Perelandra series features one planet that has never fallen (book one of the series) and one planet that is making that fateful decision when Ransom visits it (book two). (Book three takes place back on earth and I always found it much less interesting than the first two books.)

Q

more good points. but i was saying that he was shaping up as the Christ-figure. obviously, and certainly by the end of "The Last Battle" he outted himself as Christ in and for Narnia.